Throughout Panama, a silent extinction is occurring. Dozens of frog and toad species have already been driven to extinction by chytridiomycosis, the world’s most lethal amphibian disease. Fortunately, amphibian conservationists and the greater zoo community have not been sitting idly by.

Caused by the chytrid fungus, this disease is responsible for having caused amphibian population declines in North, South and Central America, Australia, Europe, Africa and more. But in Panama, a ray of hope in the form of the Atelopus limosus has been released back out into the wild.

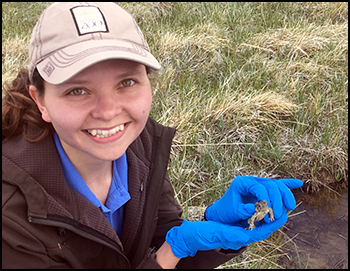

Jeff Baughman, Cheyenne Mountain Zoo’s Conservation Coordinator, was instrumental in the release, which was done in partnership with the Panama Amphibian and Rescue Conservation (PARC) Project, a program Cheyenne Mountain Zoo helped found.

Not only is CMZoo a founding partner for PARC, Baughman and other CMZoo staff have provided instrumental leadership to get the project at a point where the project can allow releases to happen. CMZoo staff assist with field expeditions and surveys, development of education programs and provide veterinary and husbandry support in Panama. This contribution has resulted in developing long-term security for Panama’s biodiversity.

PARC is truly an ark for amphibians. They partner with conservation organizations around the world to ensure the global survival of amphibians – focusing on those that can no longer be safeguarded in nature. In eastern Panama, there are 30 amphibian species that have been identified by PARC as rescue priorities.

This time, Baughman was on hand to release 90 of the Atelopus limosus, a native species more commonly known as the Limosa harlequin frog. A few years prior, only a handful of the species remained in existence.

“They’re very lucky and have a second chance,” Baughman explained. “It was nearly extinct, so we pulled the remaining few out of the wild to try and save the species.”

Baughman said conserving this particular species was difficult, as its numbers were so low. He said ideally conservationists aim to collect at least 20 males and 20 females of a species in order to generate greater genetic diversity in their offspring, yet there were so few of the Atelopus limosus collected during the first few expeditions and, their goal became simply to save it.

“We didn’t know how many other nearby sites would still have the limosus present. Time was ticking fast,” Baughman said.

The frogs were treated for the chytrid in an anti-fungal bath when they were first brought into the facility. Additionally, biosecurity is extremely important at the PARC facility. Scientists and workers disinfect any equipment or supplies that may have come into contact with the fungus, and remove shoes every time when entering the building. Baughman said humans could bring chytrid into the facility, so these precautions are necessary and crucial.

Baughman said the idea of releasing the species at lower elevations is interesting to the PARC scientists and others involved in the project because chytrid is less stable at areas that are warmer throughout the year. They released all of the frogs at the same location – within the lowland habitat, where temperatures are higher. They’re hopeful the released frogs will be able to self-treat if they happen to contract the disease again, as they’ll be in a warmer climate.

“The best case scenario we can hope for is that they survive and successfully reproduce,” Baughman said. “Even if this release trial isn’t successful this time, the information that is being collected will help not only this project, but many other amphibian programs throughout the world.”

The frogs will be tracked daily through July. There are a few frogs that have radio telemetry transmitter belts. They also have two forms of visible implant elastomer (VIE) markings for easier tracking. There are colored tags that are visible externally and are made up of a two-part elastomer material. One is an elastomer liquid that is injected into tissue with a hypodermic syringe and allows scientists to see the tags through a thin part of the frog’s skin. Within hours or days, the elastomer converts into a pliable solid and maintains the pigment in a well-defined mark, without damaging surrounding tissue or the animal.

“Think of it like a tiny fluorescent tattoo that can easily be seen under a black light,” he said.

Baughman traveled to Panama for the release itself, but also to help with the setup leading up to the release. Identifying and processing the animals took quite a bit of time, as did preparing and securing the actual release site.

There are currently 13 critically endangered frog species in human care at PARC. Baughman is hopeful for future releases for those species, as well.

Frogs are indicator animals, says Baughman. This means that if they were to go extinct in Central America, people would start to see a ripple effect caused by their absence.

“For example, you might start to see algae overgrowing in ponds, lakes and streams because there’d be no tadpoles to feed on it. That in turn would lead the PH and water chemistry to be off, so other species locally would start to suffer. Then unbalanced water would end up as runoff in the ocean and affect the species there.”

“It’s like a game of Jenga,” he explained. “You can pull one block here and there and the structure is still standing, but you’ll finally pull the one block that makes the whole thing collapse. Our ecosystem is such a delicate balance.”

To learn more about Panamanian frog conservation, please visit: http://amphibianrescue.org/