Tujoh, a 25-year-old male Bornean orangutan, recently made CMZoo husbandry training history. Tujoh and his primary trainer, Amy Tuchman, successfully completed a voluntary electrocardiogram (EKG) – a test that measures the electrical activity of the heart.

As Tujoh ages, Tuchman and the rest of his care team are looking for ways to take advantage of new technologies to diagnose medical issues common in great apes, like cardiovascular disease.

“It’s especially prevalent in middle-aged male great apes, and all of our guys in Primate World fall into that category,” said Tuchman. “This device allows us to monitor them as often as we like. Early detection could be the difference between life and death, especially for a big guy like Tujoh.”

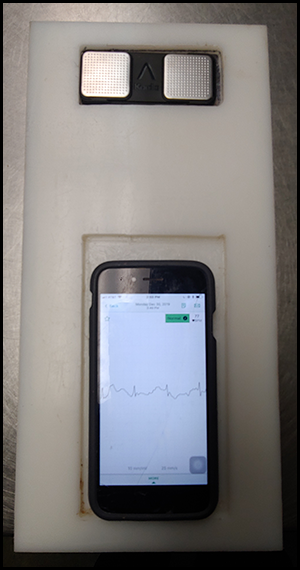

This new pocket-sized equipment is a welcome advancement for 340-pound Tujoh, who Tuchman describes as a “straight-A student.” The test requires Tujoh to place his two index fingers through the protective barrier between him and Tuchman, onto the quarter-sized metal discs that take the reading. Then, he needs to keep his fingers on the discs with consistent pressure for thirty seconds, continuously.

It only took Tujoh a month to learn how to successfully complete the test. Perhaps that’s in part thanks to his intense focus. Tuchman says Tujoh likes to maintain direct eye contact with her throughout the training.

“He learns incredibly fast,” said Tuchman. “He already knew a ‘hold’ cue, and we built the behavior from there. Once he was sitting on the other side of the mesh from me, I held up my finger and asked him to touch his finger to mine. He’d never done it before, but he got it right away.”

Tuchman cleans Tujoh’s two fingertips before he places them onto the device to ensure the best connection for the reading.

“Now he holds out each finger individually for me to clean before we start, like he’s getting a manicure,” said Tuchman, with a laugh. “He learns how to do something, and he remembers every step you’ve asked of him. Then, he wants to do it that exact way every single time.”

As with most behavior training, the trainers learn from the animals, too.

“The device is made for humans, so we needed to customize how we could present it in a way that allowed trainers to be hands-free to reward his participation,” said Tuchman. “We also needed to securely present it at a level that he could access it while sitting and relaxed on the other side of the protective barrier between us, so we could get an accurate reading.”

Compared to the oversized and complicated readers of the past, these test results will likely be more accurate, because the testing equipment and overall experience are less invasive, thus less stressful for Tujoh.

“It’s still sensitive equipment,” said Tuchman. “That’s a good thing because we know it’s picking up the tiniest abnormalities for us to track, but it also requires a lot of patience and participation from Tujoh to complete the test.”

Tuchman and her team were inspired to pursue the ability to provide regular EKGs for the great apes in their care and attended a conference with Great Ape Heart Project – a coordinated clinical approach targeting cardiovascular disease across all four non-human great ape taxa: gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees and bonobos. Studies have shown cardiovascular disease is a primary cause of mortality among great apes.

“I’m the primary keeper for Goma [28-year-old Western lowland silverback] and Tujoh, so I was interested in learning how other zoos are managing cardiac care, what tools are available and what we could do to improve our great apes’ cardiac care,” said Tuchman. “Any little improvement we can make to monitor their cardiac health and stay ahead of any issues will be really important.”

Tuchman and her team will share Tujoh’s data with Great Ape Heart Project so they can learn and share data that benefits great apes in human care around the world. They will also continue training with other great apes at Cheyenne Mountain Zoo to utilize this life-saving, non-invasive diagnostic tool with as many participants as possible.